For the complete article, click through to the July/August 2019 digital edition.

Editor’s note: Efforts by the cosmetic industry have moved beyond natural and green ingredients and processes to those that are sustainable, eco-friendly and fair-traded. But the next chapter in the naturals story moves beyond green solutions and the welfare of supply chain workers—people need access to opportunities that allow them to better their lives and communities. This article takes a step back from the bench to look at the bigger picture of how the cosmetic industry can support this move in the direction of social progress. As an aside, note that the author is not affiliated with certifiers or microfinance institutions described herein.

"Social progress is defined as the capacity of a society to meet the basic human needs of its citizens, to establish the building blocks that allow citizens and communities to enhance and sustain the quality of their lives, and to create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential."

—Michael Porter, Harvard Business School, in Measuring Social Progress1

It is interesting how sustainable development is often defined as the triple bottom line, a term introduced by John Elkington1 in the late 1990s in reference to the way Excel spreadsheets add up and measure profit or performance for a positive or negative outcome. Indeed, accounting tools are often used to measure performance in terms of profit; i.e., the sum on a balance sheet.

In contrast, prior to Elkington, Paul Hawken denounced the cost of profit in his book, The Ecology of Commerce. In it, he highlighted the lack of responsibility and accountability by businesses when considering the life of their products and the ecological impact they have on the environment.2 In short, he believed it is no longer possible to consider profit without considering impact on the environment and on society.

The environment has indeed been a centerpiece for the past 30 years, as clear and unconfutable evidence of climate change and its impact on the planet have been associated with reductions in natural resources and sustainability. This mainstream communication has been impossible to ignore. In fact, the environment is one of three elements in the triple bottom line of sustainable development, which considers the outcome of a business or product as the sum of: economic factors (profits), social equity (people) and environmental practices (planet).1

While profit is relatively easy to measure and is strictly regulated by revenue services and auditing bodies, the environmental and social parts are more difficult to measure and generally not regulated or audited. Only more recently have certification companies and consulting firms and auditors stepped in—notably, neither the government nor private sectors, both of which remain dormant—responding to pressure by media, bloggers and consumer organizations. Apparently, they see now as the right time to provide a service and help control and validate practices for those companies seeking to move in a cleaner direction toward the environment and, more recently, toward society.

According to these models, consumers decide, based on the type of certification, label and communication about sustainable development, which companies are doing the right thing in relation to the environment and society. In addition, and more recently, corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports have added information to certification labels to better understand the sustainable development performance in the private sector. But is this information enough? Do cosmetic companies and their CSR departments have the tools to succeed in each of the three pillars for sustainable development? Are these the right metrics to measure sustainable development performance?

When measurements are about the environment, reductions in carbon footprint, e.g., by using clean energy and/or green chemistry; less water consumption; and by-product recycling, to name a few, are examples of what the industry has put in place to slow the unsustainable use of resources and to limit waste and pollution that directly impact the environment. It is more complicated to measure the social performance of companies beyond how well they treat their employees. Figure 1 illustrates (see boxes) several issues that are touched upon when profits and economy intersect with society. Each of these would require measuring in order for companies to account for their impact on social progress.

Although the United Nations has created practices to follow in terms of governance for the environment—specifically, in order to protect biodiversity; e.g., the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Cartagena and Nagoya protocols—these practices are not rules and are not necessarily implemented by member states.

So, then, who is deciding the timing, the rules and the inputs for sustainable practice? Who is measuring the outcome, and how? As noted, CSR has grown, with a series of objectives toward the environment and society. But what about social progress?

Measuring Outcomes of Social Progress

Private certifiers have used protocols associated with given labels to grant a “social impact” or “ethical sourcing” certificate to cosmetic companies or suppliers that make a positive impact on communities. However, such indicators are often reduced to simply a fair trade status; sometimes without considering child labor or respect for human rights. Furthermore, a company’s social impact and consequent performance cannot be limited to fair trade or human rights, it should look at the broader impact and improvement on the community as a whole and quality of life. This, of course, is difficult to measure since targets are multiple and complicated and the outcome is less predictable than an environmental one.

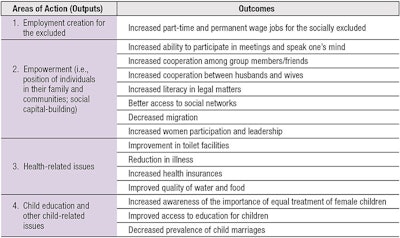

A holistic approach to social impact would also be specific to a given community, since each has different needs and goals. Thus, the intervention must be tailored and the impact will be customized. While jobs creation and fair trade are important, they are not enough since infrastructures, i.e., housing, schools, hospitals, banks, etc., and other factors (see Table 1) are also essential for community welfare and growth.

Measuring Efforts Toward Social Progress

A company’s performance toward social progress should not only be about measuring outcomes, but also the actions and corrective measures taken to bring about those outcomes. Therefore, the entire process by which impact is created must be considered. When looking at inputs, it is essential to verify what resources a company provides to support a community activity—specifically, what is the motive, i.e., charity, investment or initiative; in what form, e.g., a gift, loan or time; and for what cause, for example, education, health, etc.

Once these inputs are determined, the output (what happened) and impact (what changed) can be measured over time. Specific community outputs to measure could include: the number of activities delivered; how many people were reached; the funds raised; or the business, infrastructure or securities created. Impact or changes in the communities are measured as a result of these activities and should bring short- and long-term benefits to create a self-sustaining community with a good quality of life.3

The Finance Factor

As is often the case in modern society, formal finance has substituted informal finance, and social impact is often partly dependent on a monetary investment. Therefore, social performance indicators have traditionally been developed by agencies interfacing and collaborating with banks delivering microfinance support, local governments and nonprofit organizations, all of which work together to deliver inputs to have a positive social impact.

In relation, a Microfinance Institution (MFI) can put into place a system to target, in the best possible way, the financial need of a community; not just its own business. To contract such a service, the process should start by examining the intent and design of the MFI, then its vision and mission—including its social objectives. Next, the MFI’s systems should be reviewed to assess whether it has procedures in place that are linked to its social goals, and whether it is carrying out the necessary activities to achieve these social goals.